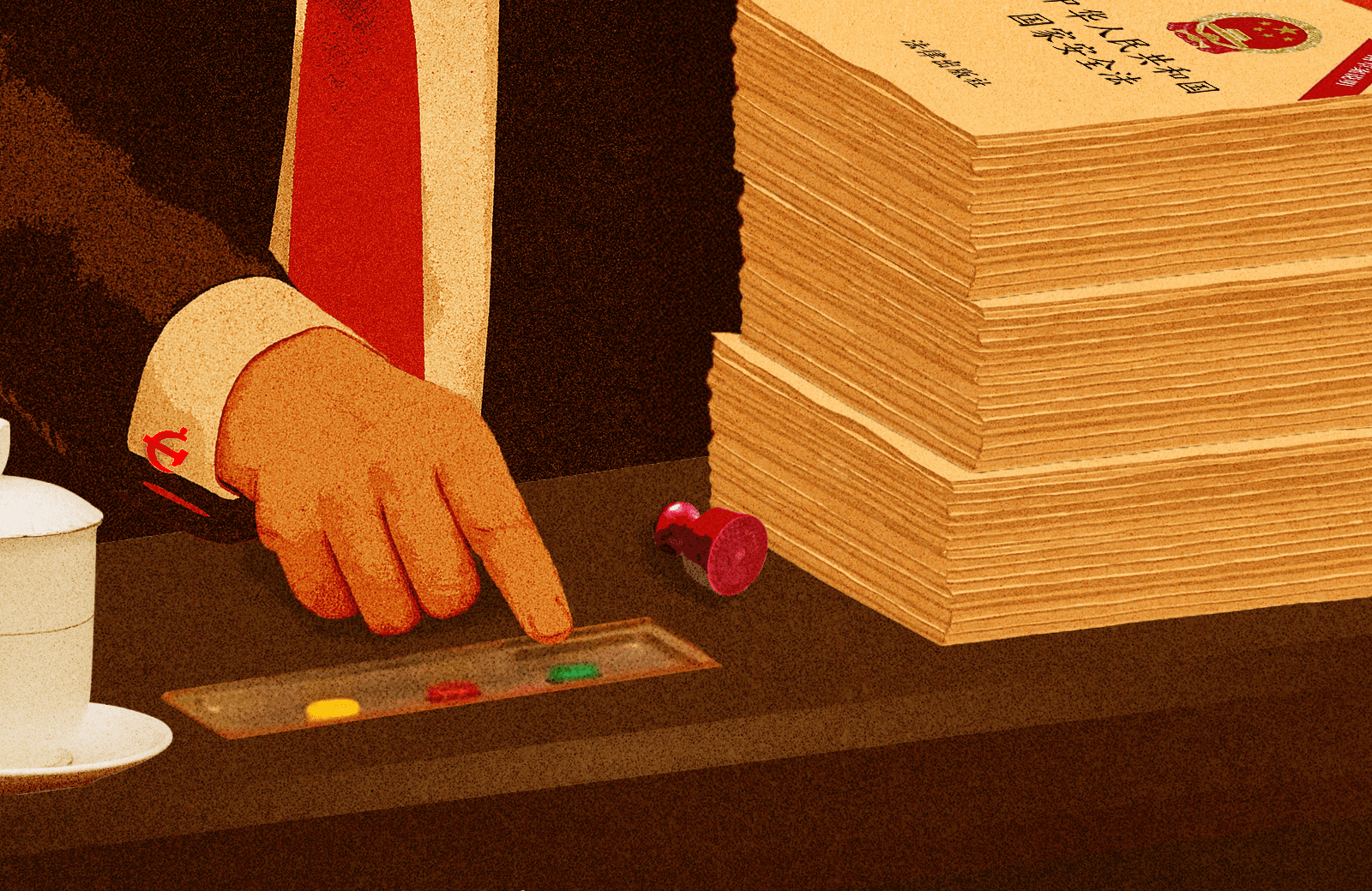

A Roadmap of China’s National Security Laws

A review of China’s national security framework reveals 16 officially designated “key” laws and 17 supporting regulations, predominantly brand new or thoroughly reimagined amid Xi’s Jinping’s New Era of National Security.

n recent years, Washington has adopted new trade and investment restrictions aimed at protecting national security, targeting Chinese companies and critical sectors. Beijing has responded in kind, rolling out its own increasingly strict national security laws—some of which can penalize companies for complying with U.S. rules and others which place Chinese companies and individuals in dubious positions as potential agents of the State. This dynamic creates a growing compliance challenge for multinational firms: actions taken to follow U.S. law may conflict with Chinese law, and vice versa.

WireScreen, the leading China-focused data analytics platform, publishes essays like this to help clients navigate that tension—understanding not only the U.S. requirements they must meet, but also the legal and political environment in which they operate in China. This essay tallies up Beijing’s current national security framework, which the Chinese government has publicly articulated as part of a broader geopolitical contest with the West.

China’s State Council Information Office (“SCIO”)—the country’s international publicity agency—illustrates the Party-state’s integrated structure: it sits under the State Council but is also directly supervised by the Chinese Communist Party’s external propaganda working group.

On May 12, 2025, the SCIO published a document called China’s National Security in the New Era.1 This document attracted attention because it represents the most updated articulation of China’s narrative on national security to the world. Following a recitation of key ideological concepts, the document identifies 16 “leading or key” national security laws in chronological order.

The following is a synopsis of these 16 laws with an emphasis on their application to foreign (non-Chinese) entities. We also added 17 more laws, regulations, and other normative documents of importance to China’s national security legal regime which were not mentioned.

National Security Doctrine

Important Chinese policy is molded by a theme enshrined in the name of the paramount leader for a given time period. Such themes are often stacked up over time to reflect historical progression. In the realm of national security, the following eponymous doctrines are considered key:

Notably, most of the laws that follow were ushered in (or substantially upgraded) following Xi Jinping’s articulation of China’s New Era of National Security.

National Security Law2

The National Security Law is a framework type of Chinese law in that it is light on operative provisions such as specific permissions, prohibitions, procedures, and penalties. Instead, it is more of a compendium of policies, containing aspirational goals and setting out all possible national security subjects for categorization within a hierarchy of numerous government agencies. Article 15 is a good illustration of a standard policy statement contained therein:

This type of statement is repeated in some fashion throughout the document by application to myriad national security subjects.

Chapter 6 of this law attracts international attention because it covers “duties and rights of citizens and organizations.” Specifically, Article 77, which require all persons (including companies) under Chinese jurisdiction to:

Such open-ended provisions are not surprising for a policy framework document of this nature.

Counter-Terrorism Law3

The Counter-Terrorism Law defines terrorism, sets out procedures as to how terrorist organizations are designated, and creates obligations for all levels of government, commerce, companies, and individuals for safeguarding against terrorism. The law is heavy on investigation procedures, prosecution mechanics, and penalties for violations.

A number of provisions in this law catch international attention such as mandates for facial recognition nationwide and obligations on telecommunications and internet providers to monitor and control content, and provide “technical interfaces, decryption and other technical support assistance.”

Notably, a set of implementing rules and “de-extremification” rules were issued under the Counter-Terrorism Law in 2017 and 2018 exclusively for Xinjiang.4 Those provisions equal the size of the law itself, emphasizing the importance of this area. They are very particular and delve into issues such as religious practices, dress, and various education matters.

Foreign NGO Law5

The Foreign NGO law addresses a long-standing gap on the regulation of NGOs operating in China. Previously, Foreign NGOs operated in a gray area in China, often registering as commercial businesses, representative offices, or getting special permission from the Ministry of Civil Affairs to conduct their activities. This law defines Foreign NGOs to include not-for-profit, non-governmental social organizations such as foundations, social groups, and think tank institutions. The operation of these entities is now integrated into China’s national security framework by way of mandated government partnerships, restricting activities to non-sensitive fields, and imposing severe penalties for non-compliance.

Cybersecurity Law6

The Cybersecurity Law is China’s comprehensive network security law covering all participants involved in construction, operation, maintenance, or use of networks within the territory of China. The provisions capturing the most international attention include data localization requirements (China source data must stay in China), an approval regime for cross-border data transfers, national security reviews for broadly defined “critical information infrastructure”, access and decryption, and restrictions on foreign technology. This law also forms part of China’s data control "triad" together with the Data Security Law and Personal Information Protection Law (discussed below).

Focusing on data itself, this law places obligations on all data handlers and boasts extraterritorial jurisdiction. Of international interest is an export control regime for data, especially undefined “important” data as well as special prohibitions for foreign government authority recipients of China sourced data.

The PIPL is similar to other frameworks such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”), is also extraterritorial, provides for specialized export controls on personal information (PI), and provides for entities outside of China to appoint specialized entities within China to handle PI reporting for them.

Under the cybersecurity "triad" are several implementing rules such as the Regulations on Network Data Security Management, Regulations on Promoting and Regulating Cross-Border Data Flow, Measures for Data Security Management in the Field of Natural Resources, Measures for Data Security Management in the Field of Industry and Information Technology, Measures for Civil Aviation Data Management, Regulations on the Security Protection of Critical Information Infrastructure, and others.

Starting in 1999, China began specific regulation of encryption.11 At that time, foreign encryption was basically banned for import into China for commercial use, inspection rights over source code materials were available12, and encryption keys were considered a part of State Secrets (see below for the State Secrets Law). These policies were modernized in the form of the Encryption Law. The current regime categorizes encryption into core, common, and commercial categories for separate regulation. While the new regime provides national treatment for foreign encryption, remnants of the former policy persist with regard to certification of commercial encryption, random inspections, and prohibitions against using encryption to endanger “social public interest, the rights and interests of others, etc.”13

These rules generally provide that all manner of network security vulnerabilities such as bugs, patches, and backdoors be first reported to certain state agencies before they can be publicized. A de facto approval process is mandated before publication can occur and before publication outside of China is allowed.

Nuclear Safety Law15

Apart from establishing an overall safety framework, this law governs national security reviews for foreign investment in the field (like a merger control mechanism) and maintains a “negative list” for foreign involvement.

National Intelligence Law16

The National Intelligence Law is short compared to its counterparts above and is similar to the National Security Law as it is mostly a set of aspirational goals and other policy statements. The small number of specific violations contained therein are for obstructing intelligence work, leaking of state secrets, impersonation of intelligence personnel, and abuse of intelligence authority. Article 7 of the law made international press because it states that all Chinese organizations and citizens “shall support, assist, and cooperate with national intelligence efforts” but there are no implementing provisions about this, and it is well known that these persons can be coerced into cooperation absent such a provision.

Hong Kong National Security Law17

Article 23 of the Hong Kong Basic Law (the 1997 rules governing the handover of Hong Kong to China) long required Hong Kong to create national security legislation. This was attempted and eventually postponed due to public reaction. The Hong Kong National Security Law in effect by-passed this mechanism and led the way to Hong Kong’s own national security ordinance (in 2024). The law has extraterritorial reach and provides for several key crimes such as secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces.

Export Control Law18 and Related Provisions

The Export Control Law is short but very similar in concept to the U.S. EAR. It governs exports, deemed exports, re-exports, transit, etc. of dual use items utilizing a controlled items list, a controlled entities list, licensing, and end-use checks. This is also the law under which rare earth exports are curtailed and which limits are placed over end-use checks conducted in China by other countries. A separate regime exists for the import and export of technology which regulates technology based on its sensitivity rating.19 Also, the Foreign Trade Law20 governs matters such as market access, other non-tariff measures, and state subsidies, while the Import and Export administrative provisions21 govern such matters as retaliatory tariffs on US goods.

National Defense Law22

Apart from addressing organization of the government and populace in matters of war and defense, the National Defense Law codifies China’s Military Civil Fusion Program. Nationwide enterprises and institutions are directly included in national defense tasks, and the relevant industries “shall implement the principles of integrating the military and the civilian sector.” The power of the State is directed to fully utilize the resources of the whole society, with particular emphasis on high technology industries to support the national defense.

Biosecurity Law23

The Biosecurity law sets out a comprehensive framework regarding infectious disease controls, laboratory security and security over biological R&D, special controls over the field of human genetic research and collection, bioterrorism, and biological weapons. Comprehensive controls are provided for the prevention of direct and indirect foreign contact with Chinese human genetic resources.

Land Borders Law24

Recognizing the disputed and even militarized nature of some of China’s border areas, the Land Borders Law places much emphasis on a policy to promote the creation of infrastructure and communities along border areas and border zones. These provisions also suggest an evolving state of demarcation with obligations on individuals to turn over historical materials relevant to borders, direct involvement of the community concerning border development and integrity, including rewards for outstanding border contributions. According to Article 15, border issues shall be settled through negotiations and “properly resolve border issues left over from history.” Illegal border crossings attract unspecified penalties “according to other laws” and the use of force is authorized.

Counterespionage Law25

The Counterespionage Law is probably most well-known for the dawn raids conducted on professional services and due diligence firms in 2023 (e.g., Mintz Group, Bain and Company, and Capvision). The law is probably also most often cited for its provisions that explicitly require all Chinese citizens and organizations (including foreign businesses operating in China) to support and assist the State with counterespionage tasks. The law also includes provisions regarding responsibilities on the media and online platforms to assist in promoting counterespionage education. While not unique to this law, among the list of items used to define “espionage”, conducting “other” espionage activities is among them. The law is slightly more expansive than other laws in its use of “others” and “in accordance with other law” provisions regarding the expansive powers of the Ministry of State Security.

Foreign State Immunity Law26

The Foreign State Immunity Law’s revisions in 2023 relaxed the amount of immunity foreign nations have from Chinese lawsuits. Using a restricted immunity approach, immunity is deemed waived for certain commercial activities having a “direct effect” in China, labor relations, torts, and IP matters. Article 21 notably imposes reciprocity in the event a foreign nation provides less immunity to China.

State Secrets Law27

Originally adopted back in 1951, the State Secrets Law stands as the first national security law since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. The original version (at the time in provisional form) emphasized the revolutionary context of the time, seeking to root out domestic and foreign spies, “counter-revolutionaries”, and “saboteurs”.20 The definition of state secrets in this version included all state affairs not yet decided on and if decided, not yet announced. Of course, there was also a catch-all category for “all other state affairs that should be kept secret.”21 Rewards were also provided for those safeguarding state secrets in the face of the enemy, those who report and crack down on others, remedy information leaks, and encourage others to protect state secrets. Interestingly, there was no mention of the CCP in this version, such authority being implicit, with only explicit reference to the state counterparts of government branches as they then existed.

The 2024 version places the CCP upfront and even identifies the specific CCP working group charged with leadership over state secrets. The definition of state secrets is completely modernized: along with tighter categories, leaked information must be of harm to the national interest as a prerequisite, and designations for levels of secrecy and their terms in years are specified. The current version is also revamped to address digital information, network operators, and other electronic infrastructure. Penalties for leaking state secrets notably emphasize the confiscation of unlawful gains obtained.

In its supplementary provisions, a separate category of “work secrets” is retained from earlier drafts. These can include all manner of internal procedures and working papers of government agencies.

Food Security Law30

The Food Security Law provides a comprehensive legal framework over such issues as self-sufficiency, control of cultivated land, production, reserves, distribution, processing, emergency situations, and conservation.

The following laws were omitted from the 16 leading national security law list but are directly relevant to the field (other laws and regulations directly related to 16 leading laws are incorporated into the sections above).

Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law31

The Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law is notable for its policy statements and for setting out a legal basis for the now well-known Unreliable Entity List.32 The policy is expressed as follows:

In addition to the creation of the Unreliable Entity List, the law indicates that the following individuals or entities associated with listed entities can be penalized: (1) spouses and immediate family members, (2) senior managers or actual controllers (者实际控制人), (3) other entities where listed individuals serve as senior management, and (4) other entities actually controlled, co-founded, or operated by listed individuals or entities. Penalties can include restrictions on visas, deportation, asset seizure, blocking of transactions, and “other necessary measures”.

Foreign Relations Law33

The Foreign Relations Law reads more like a long list of aspirational policy goals and codifies certain long-standing and developing foreign policy doctrines. Two main areas that stand out among these are the “Three Global Initiatives” (三大全球倡议) and the “Foreign-related Rule of Law” (涉外法治).

The Three Global Initiatives include the Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Security Initiative (GSI), and Global Civilization Initiative (GCI). These initiatives were announced by Xi Jinping over the last five years at various high profile international venues to articulate China-led foreign policy projects. The GDI is mainly around support of the developing world, the GSI is viewed by some commentators as a call for an alternative to a U.S. dominated world order, and the GCI is characterized by some commentators as China’s interest in more actively projecting its own brand of soft power.

The Foreign-related Rule of Law is a foreign policy concept involving the idea of a bridge between the Chinese domestic legal regime and the international legal system. Certain commentators have suggested that this entails the implementation of more Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law type of measures and future extraterritorial application of Chinese law. The initiative also involves projects to revise all Chinese laws relevant to foreign contact for purposes of implementing this new approach.

1新时代的中国国家安全 http://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/zfbps_2279/202505/t20250512_894771.html.

2中华人民共和国国家安全法, adopted at the 15th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People's Congress on July 1, 2015, effective from July 1, 2015.

3中华人民共和国反恐怖主义法, adopted at the 18th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People's Congress on December 27, 2015, effective from January 1, 2016, amended on April 27, 2018.

4See 新疆维吾尔自治区去极端化条例.

5中华人民共和国境外非政府组织境内活动管理法, adopted at the 20th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People's Congress on April 28, 2016, effective from January 1, 2017.

6中华人民共和国网络安全法, adopted at the 24th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People's Congress on November 7, 2016, and effective from June 1, 2017.

7中华人民共和国数据安全法, adopted at the 29th meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress on June 10, 2021.

8中华人民共和国个人信息保护法, adopted at the 30th meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress on August 20, 2021.

9See 网络数据安全管理条例, 促进和规范数据跨境流动规定, 自然资源领域数据安全管理办法, 工业和信息化领域数据安全管理办法(试行), 民用航空数据管理办法, 关键信息基础设施安全保护条例.

10中华人民共和国密码法, adopted at the 14th Session of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress on October 26, 2019.

11See Directive 273, 商用密码管理条例 中华人民共和国国务院令(第273号), October 7, 1999.

12Other provisions have also raised the issue of source code disclosure such as the Regulations on the Protection of Computer Software. See administrative practices under 计算机软件保护条例.

13社会公共利益、他人合法权益等.

14网络产品安全漏洞管理规定.

15中华人民共和国核安全法, adopted at the 29th Session of the Standing Committee of the Twelfth National People's Congress on September 1, 2017.

16中华人民共和国国家情报法, adopted at the 28th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People's Congress on June 27, 2017, and effective from June 28, 2017. Amended at the 2nd Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress on April 27, 2018.

17中华人民共和国香港特别行政区维护国家安全法, adopted at the 20th Session of the Standing Committee of the Thirteenth National People's Congress on June 30, 2020.

18中华人民共和国出口管制法, adopted at the 22nd Session of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress on October 17, 2020.

19See 中华人民共和国技术进出口管理条例.

20See 中华人民共和国对外贸易法.

21See 中华人民共和国进出口管理条例..

22中华人民共和国国防法, amended at the 24th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress on December 26, 2020, effective from January 1, 2021.

23中华人民共和国生物安全法, adopted at the 22nd Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress on October 17, 2020, effective from April 15, 2021.

24中华人民共和国陆地国界法, adopted at the 31st Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress on October 23, 2021, effective from January 1, 2022.

25中华人民共和国反间谍法, revised and adopted at the 2nd Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 14th National People's Congress on April 26, 2023, effective from July 1, 2023.

26中华人民共和国反间谍法, revised and adopted at the 2nd Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 14th National People's Congress on April 26, 2023, effective from July 1, 2023.

27中华人民共和国保守国家秘密法, revised and adopted at the 9th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 14th National People's Congress on February 27, 2024, effective from May 1, 2024.

28国内外间谍分子,反革命分子和破坏分子.

29其他一切应该保守秘密的国家事务.

30中华人民共和国粮食安全保障法, adopted at the 7th Session of the Standing Committee of the 14th National People's Congress on December 29, 2023, effective from June 1, 2024.

31中华人民共和国反外国制裁法, adopted at the 29th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Thirteenth National People's Congress on June 10, 2021.

32不可靠实体清单, published by the Ministry of Commerce in bulletin form.

33中华人民共和国对外关系法, adopted at the 3rd Session of the Standing Committee of the Fourteenth National People's Congress on June 28, 2023.